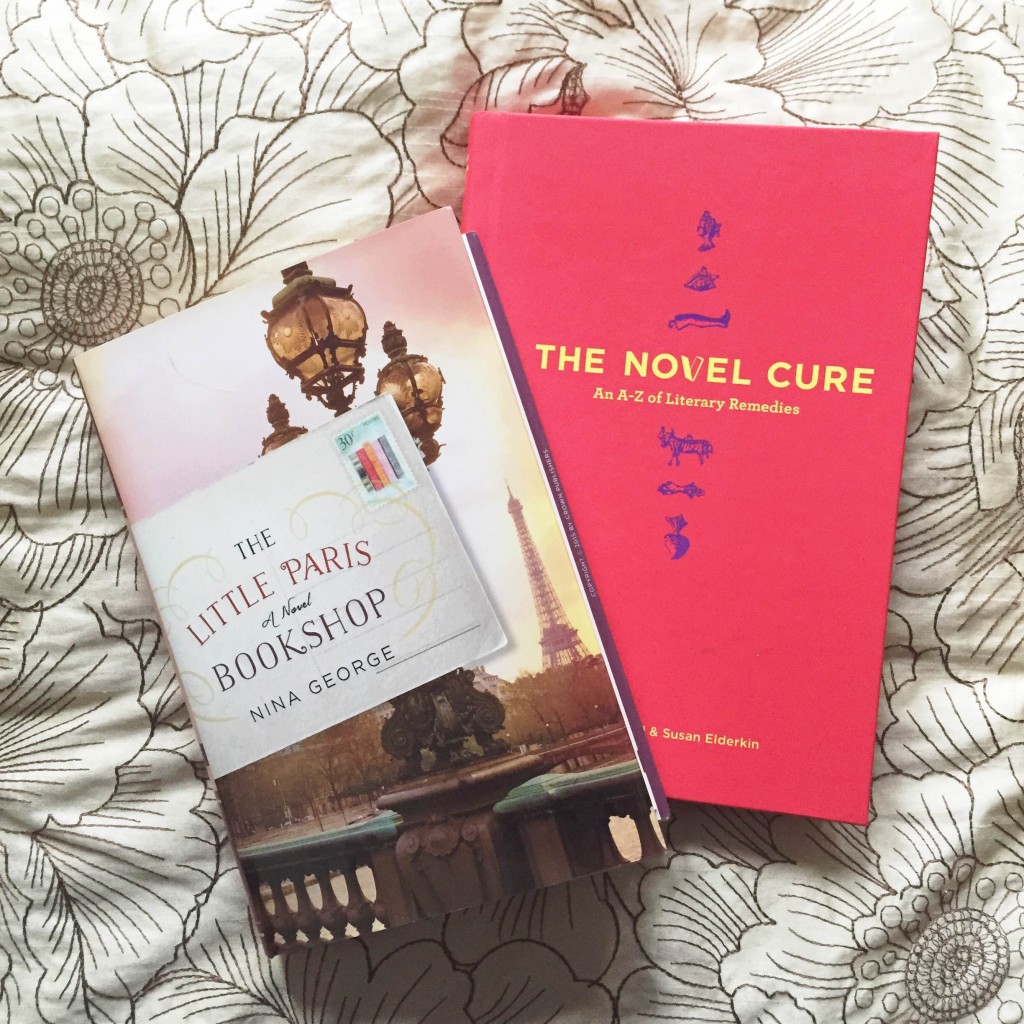

The Little Paris Bookshop by Nina George. Crown, out now.

[I received this book from Random House Canada in exchange for an honest review; this did not affect my opinion of the book whatsoever.]

The Little Paris Bookshop is the story of Jean Perdu, who runs a book barge in the Seine called The Literary Apothecary, where he specializes in prescribing books for people’s emotions, fears and interests. But as good as Jean Perdu is at reading other people, he’s quite incapable of reading himself, as he’s also on a quest for answers, forgiveness, love and purpose.

The book was slightly misleading, at least from my point of view of what drew me to it. I saw a book about books (done deal), a letter on the cover (c’mon) and totally romanticize the idea of a book barge in Paris (srsly). While these all come in to play, the book is hardly about the shop. It’s about Jean completely destroying himself only to try to build himself back up again.

You see, his once-love, Manon, left him over 20 years ago, and he still hasn’t gotten over her. He lives in an apartment stripped of all substance but still full of memories. It isn’t until he somehow develops a crush on his housemate that he’s triggered into a series of events, taking him on a quest down France’s waterways on the boat with a famous, tortured 20-year-old writer and an Italian chef. Three sad, romantic dudes on a boat. Oh, there are some stray cats who jumped onto the boat, too.

So while I was originally quite interested in The Little Paris Bookshop, by the last third, I couldn’t quite tolerate the characters anymore. I found them to be whiney, repetitive and boring. If I’m going to read a book about adventures in a boat down a river, I’d also hope the adventures are a bit more exciting. Do exciting boat things happen in France?

What I really loved about The Little Paris Bookshop was any scene of Jean Perdu predicting books for people and Nina’s prose. Some favourite passages:

Perdu asked the customer, whose name was Anna, a few questions. Job, morning routine, her favourite animal as a child, nightmares she’d had in the past few years, the most recent books she’d read… and whether her mother had told her how to dress.

Personal questions, but not too personal. He had to ask these questions and then remain absolutely silent. Listening in silence was essential to making a comprehensive scan of a person’s soul.

*

A bookseller never forgets that books are a very recent means of expression in the broad sweep of history, capable of changing the world and toppling tyrants.

Whenever Monsieur Perdu looked at a book, he did not see it purely in terms of a story, minimum retail price and an essential balm for the soul; he saw freedom on wings of paper.

*

“Women tell you more about the world. Men only tell you about themselves.”

*

Autumn was on its way, bringing visitors who preferred to build castles out of books rather than sand. This had always been his favourite time of year: new publications spelled new friendships, new insights and new adventures.

There is a book that is basically the book version of the Literary Apothecary, and it’s called The Novel Cure: An A-Z of Literary Remedies. So, keeping with theme, here are some of its literary suggestions for Jean Perdu’s ailments.

Anger: Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (ha!); “Sometimes we all go out too far, but it doesn’t mean we can’t come back.”

Being Antisocial: Anne Tyler’s The Accidental Tourist and Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle. “Being not the most sociable person in the world doesn’t have to mean you’re a sad excuse for a human being.”

Bitterness: Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko. “People tend to shun bitter characters — in life as well as literature — as they exude anger and ill will.”

Broken Heart: Niall Williams’ As It Is in Heaven and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. “It’s vital to grieve when love is lost. Drop out for a while to do it.”

Depression: Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, Rebecca Hunt’s Mr. Chartwell and Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot. “In serious cases, bibliotherapy is very unlikely to be enough.”

Dissatisfaction: John Steinbeck’s Cannery Road, an “ode to the ambition-free life of the bum.”

Loneliness: Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights, Robert Graves’ I, Claudius and Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City. “You need never be lonely with a roomful of novels — or even just the one you’d take with you to a desert island — and we all have our favourite literary friends.”

Midlife Crisis: Kingsley Amis’ Girl, 20, Arto Paasilinna’s The Year of the Hare and Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding. “Sometimes, a midlife crisis can be a welcome wake-up call.”

Regret: Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City and Nancy Turner’s These Is My Words: The Diary of Sarah Agnes Prine. “…regret derails; it paralyzes and prevents.”

Yearning: Alessandro Baricco’s Silk. “Do not prize what you do not know above what you know.”

I don’t think The Little Paris Bookshop was bad, I just think that a) maybe I’m not the right kind of person to read this and b) the book could have been presented/marketed a bit differently. Though I felt disappointed by the end, I’m still glad this book got me through a reading dry spell, so look, Jean Perdu helped one more person.